The editor of the Health Service Journal was in Roy Lilley’s virtual hot seat in November. He looked back over almost 20 years’ of editing the NHS’ most prestigious policy and management journal, ranked the seven health secretaries he has seen come and go, and looked ahead to the end of the coronavirus emergency – in spring 2022.

Alastair McLellan has been editor of the Health Service Journal for the best part of twenty years. As he told commentator Roy Lilley, after training as a journalist and working for the construction press, he arrived just as the 2002 Budget delivered a “kiss of life” for the NHS.

After almost two decades of Conservative administrations, New Labour had been elected on a pledge to maintain Tory spending limits. But a ‘winter crisis’ in 2000 pushed prime minister Tony Blair into promising to raise health spending “to European levels”; to the fury of his chancellor, Gordon Brown.

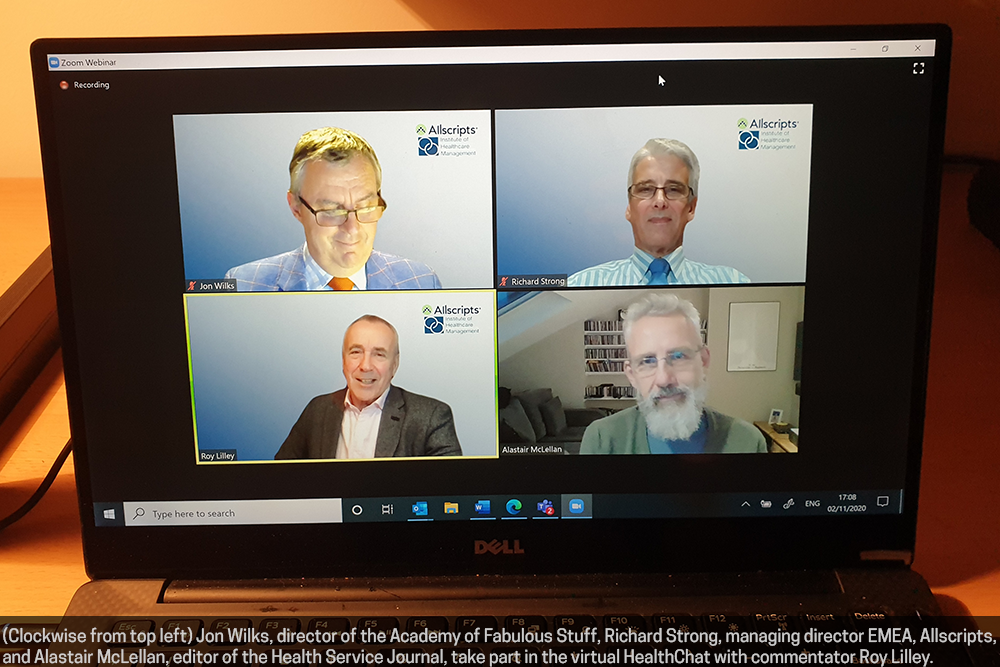

The 2002 Budget delivered with five-years’ worth of 7.4% real-terms funding increases. “I arrived the week before the Budget delivered the biggest increase in funding for a specific set of services we have seen or that we will ever see,” McLellan told Lilley in his latest HealthChat, sponsored by Allscripts UK.

“[The government] doubled the funding available to the NHS over ten-years [1997-2008]. Even then, I knew I would not see anything as significant. Covid is up there, but it doesn’t match it, because without that Budget I do not think we would have the NHS now. The compact with the British people would have been broken, and there would have been a different kind of system.

“So, I had to sit down and write an editorial, and as I did that I thought ‘I am not up to this task. I have been here for two weeks and I have no credibility or credence as a health journalist’.” The job got done, but McLellan admitted there might have been more than a few clichés in what he wrote.

Worst health secretary…

Having promised huge sums of money for a health service struggling with a huge waiting list, dilapidated estate, demoralised staff and little or no technology, the government had to work out how to spend it.

It captured staff and public ideas in The NHS Plan and laid out a reform programme in a second document, Implementing the NHS Plan, that bore the fingerprints of then-health secretary Alan Milburn and his advisors, Paul Corrigan and Simon Stevens.

Still, Lilley suggested: “Lots of people say that the money was wasted.” McLellan didn’t agree with this. “A lot of money was spent very fast, and if you do that you will waste quite a lot of it,” he said. “But if they had taken longer to do it, or spent less, then [not only would the service have continued to deteriorate but] it would not have coped with austerity.

“The NHS went into austerity [the Conservative belt-tightening imposed after the financial crash of 2008] with some fat on it, and it lived on that fat for five-years.”

Unfortunately, over this period, it also had to cope with what former NHS chief executive Sir David Nicholson called “a re-organisation so big you can see it from space” – the wholly ill-judged shake up launched by Milburn’s successor but five, Andrew Lansley.

Putting to one side Andy Burnham, who barely spent any time in the job, and was distracted by his tilt at the Labour leadership, McLellan said he would put “dear old Andrew Lansley” bottom of his personal ranking of health secretaries.

“His story was a Greek tragedy,” he argued. “I knew him well as shadow health secretary, when he spent his time going out and asking people what they wanted, so he could arrive [in post] with a plan, but because of the banking crash [that plan] was completely irrelevant.

“He wasn’t a good enough politician to pivot, and everybody else was looking elsewhere, so nobody stopped it, and it was a disaster.” Lansley’s reforms, outlined in the 2010 Liberating the NHS white paper, dismantled the health service’s regional structures, introduced clinical commissioning groups, and tried to ginger up competition among providers through ‘patient choice’.

In other words, they instituted the system that Simon Stevens, who spent the austerity years in the US, has been trying to unpick since he returned to the UK as chief executive of NHS England in 2014. But without the money or legislative time that was available to Milburn in the early 2000s.

Best health secretary…

For most of this, more recent, period of NHS history, the health service has been led by Jeremy Hunt. After rapidly running through Milburn’s successors – John Reid, Patricia Hewitt and Alan Johnson – McLellan picked Hunt as his second-best health secretary.

“I think he realised, once Stevens joined, that he had to stay out of his way, so he needed another cause, and he picked patient safety,” McLellan said. “That gave him a political advantage, because Mid Staffs meant he could use it to kick Andy Burnham [who resisted calls for an inquiry into the trust that he also passed for ‘foundation’ status].

“But he stuck with it, and he didn’t have to do that.” Hunt did more than stay out of Stevens’ way. He backed the Five Year Forward View and the NHS Long Term Plan, with their focus on population health management and integrated care, and he managed to get a substantial “birthday present” to mark NHS70.

Which, while it wasn’t the 2002 Budget, was still worth having. “If the NHS had not had that money, and Covid had turned up, then bloody hell…” as McLellan put it. Even so, it is Milburn who sits at the top of the HSJ editor’s health secretary rankings.

“He was just fantastically good at getting things done,” he told Lilley. “He saw down the Treasury, he saw down Gordon Brown, he got the money. It was the most important thing in the NHS since its creation.”

Bloomberg for the NHS in England

The NHS is not the only institution that has changed in the 18.5 years of McLellan’s tenure as HSJ editor. HSJ has also changed substantially. When McLellan arrived, what had been a rather stolid magazine was still coming to terms with its sale by MacMillan Publishing to the much brasher EMAP, which introduced more commercial content, before selling it on to The Guardian Media Group.

Under GMG’s ownership, paper publication was phased out, and HSJ went online. Around this time, McLellan told Lilley, he took a conscious decision to “stop doing lots of things” that the magazine had been doing, such as long-form features, case studies and profile interviews.

“Our team is twice the size it was when I began, but we focus on a much narrow set of things: reporting on and analysis of the English NHS,” he said. “About eight years ago, I talked about wanting to be Bloomberg for the NHS, because it is a £1 billion industry, and nobody was covering it properly.”

More recently, HSJ was sold to Wilmington plc, which substantially increased its focus on data gathering and presentation. Still, it’s the online news service for which HSJ is best known. Lilley asked how it manages to strike a balance between getting access to politicians and holding them to account and between covering the NHS and challenging it.

“We do not take a stance,” McLellan said. “We just try to be right about the facts. We are cautious about reporting things that we are hearing without triangulating them, but we will spot things first – and when we do, we will call them out.”

Covid, Covid, Covid

In line with this, McLellan was reluctant to take a stance on the present health and social care secretary, Matt Hancock, who only took over from Hunt eighteen months ago, and now finds himself with “the impossible job” of balancing Covid public health demands with pushback against another, extended lockdown.

Having said that, he acknowledged that Hancock “doesn’t make things easy for himself” with his over-enthusiastic style of presentation. “There are lots of good things he is doing, fighting the NHS’ corner, but they are undermined by over-promising,” he said.

And Covid is likely to be the focus of the NHS for a while yet. Asked by Lilley where the health service will be in three-years’ time, McLellan said it was impossible to predict, unlike the next year, which is easy.

“We will have a difficult winter; how difficult will depend on flu, the weather, lockdown,” he said. “Lockdown will squash [Covid] a bit, but it will come back around Christmas, so we will need another squash. Vaccines will come in for frontline staff, but they will have limited impact.

“So that will get us to the summer when, hopefully, Test and Trace will be better, and there will be a vaccine. That will buy us a bit of time, which will get us to the autumn, after which there will be another difficult winter, but the spring of 2022 will be… better.

“Somebody said to me recently that October 2021 will be a lot more like October 2020 than October 2019, so spring 2022 is when I will start to plan foreign holidays again.”